How can we measure the success of hacktivists? Certainly, achievement of a desired political change is the choice outcome. But seeking a non-zero metric, let’s consider the amount of media coverage an organization receives to be a yardstick for success.

We’ll look specifically in this post at media attention, both mainstream and social, to the work of prominent hacktivist groups. These include some of the best known such as the Syrian Electronic Army (spoiler: the most successful at garnering media attention) and RedHack as well as lesser known groups like the Bangladeshi Grey Hat Hackers and Robot Pirates.

Importantly, Anonymous is not included in this analysis. By volume, Anonymous is far and away the most talked about hacktivist “organization” although lack of an understood structure makes it difficult to determine where a formal group begins and ends. Due to the resulting amount of noise, we decided to focus on more defined groups; an analysis of Anonymous operations makes for another project!

Using Recorded Future web intelligence data, we measured and plotted the cumulative media references (~27,000 in total) to 28 hacktivist groups during a four and a half year period (Jan 1, 2009-July 31, 2013) to determine: a) which groups have achieved the greatest level of visibility over time, and b) what events drove high levels of media attention to a group.

Media references to prominent hacktivist groups – January 2009 to July 2013

Note: The Y-axis uses a log scale to describe the cumulative references to each organization.

How They Stack Up

Topping the charts for total references during the measured time period (by nearly a factor of 10) was the Syrian Electronic Army. The SEA made a massive impression during the first six months of 2013 by hacking and disrupting some of the world’s highest profile media entities, many of which would go on to report on the group’s operations.

Lesson? Hack the media if you want attention.

Three groups fall closely as the next most visible groups in terms of cumulative media attention during this 4.5 year period: An0nGhost (distributed), Comment Crew (China), and RedHack (Turkey). Three very different groups claiming distinct goals ranging from pro-Islam propaganda to state cyberespionage to domestic political protest.

In the case of those three groups, we find the temporal element especially interesting to examine since the growth in attention peaked at different for each hacktivist organization.

An0nGhost

Making its first media impressions during January of 2013, this collective of hackers led by Mauritania Attacker initially drew attention for its hacks on export.gov as well as a variety of Israeli and Filipino websites. What you’ll notice in the graph is a surge in attention to An0nGhost during May 2013, which was driven by attacks on hundreds of websites as part of the coordinated #OpUSA campaign.

Lesson? Make a big splash by promoting plans to hit high profile targets along with a myriad of hacktivist friends

Comment Crew

With its operation popularly known as APT1, security company Mandiant released a bombshell report during February 2013 linking the Comment Crew to “China’s 2nd Bureau of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Staff Department’s (GSD) 3rd Department (Military Cover Designator 61398).”

Lesson? Evidence of state-backed operations leads to significant media attention.

RedHack

This group of Turkish hackers drew attention as far back as mid-2011 but suddenly achieved a much higher profile when it backed physical demonstrations against the Turkish government in June 2013 and found itself intertwined with operations claimed by Anonymous. That month, the group claimed successful attacks against several high profile targets including defacement of the Istanbul Special Provincial Administration website and hacking the email of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Lesson? Make an impact during sociopolitical events already in the eye of the mainstream media.

Summary

The relative attention for these groups is interesting to compare on its own, but we can also learn from each set of circumstances that led to the campaigns noted above for their media impact.

In Turkey, we saw RedHack provide yet another example of hacktivists supporting social unrest on the ground with parallel efforts in cyberspace. The targeting of government assets could very much have been anticipated and should be expected in future scenarios.

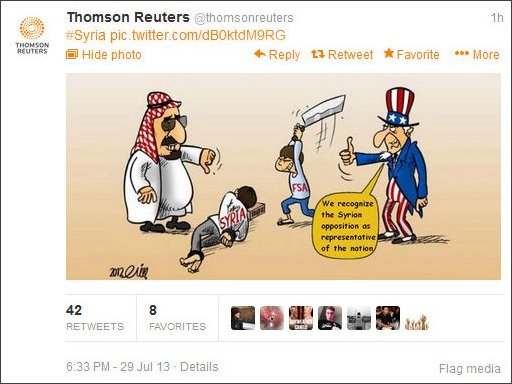

With regards to the SEA, their work amounts to a guerrilla public relations campaign to put pro-Assad propaganda in front of Western readers. Leveraging insecure channels owned by big media organizations allowed the group to make a high impact without the need for particularly sophisticated technical capabilities.

Finally, the organizations with less attention can serve as interesting cases whether they happen to be focused on regional causes (Jember Hacker Team, Pinoy Vendetta) or even ceased operations permanently or temporarily (Teamr00t, Iranian Cyber Army).

There’s much more that can be done to analyze each of these groups from more in-depth targeting research to an investigation of the technical indicators and capabilities associated with a particular organization or operation. Visit us at Recorded Future to learn more about the data used in this study of media success for hacktivist groups as well as additional applications of Recorded Future for threat intelligence.